The Kinsey Scale and the Sexual Spectrum: Are We All Bisexual?

Human cognition often simplifies reality, frequently reducing complex concepts like sexual orientation to binary categories. The Kinsey Scale, developed by Alfred Kinsey, fundamentally challenged this dualistic thinking, proposing a spectrum of sexuality that acknowledges numerous intermediate degrees between heterosexuality and homosexuality.

Rethinking Sexual Orientation

Alfred Kinsey revolutionized the understanding of sexual orientation by proposing a model that acknowledges numerous intermediate degrees between exclusive heterosexuality and exclusive homosexuality. This groundbreaking concept was formalized in what is now known as the Kinsey Scale.

Questioning Dicotomous Sexuality

Historically, sexual orientation has often been perceived as a dichotomy: heterosexuality or homosexuality, where one negates the other, frequently framed as cultural constructs rather than biological realities. Yet, in the first half of the 20th century, biologist and sexologist Alfred Kinsey extensively challenged this rigid categorization. His 15-year study led him to conclude that the labels of “homosexual,” “bisexual,” and “heterosexual” were too restrictive and limiting. Kinsey’s research consistently found that intermediate states of sexual orientation were far more prevalent than previously assumed. Consequently, he proposed a broad spectrum of sexual orientation, a multi-degree scale ranging from pure heterosexuality to pure homosexuality, encompassing various intermediate categories. Essentially, the Kinsey Scale transformed the qualitative classification of sexuality into a quantitative description, akin to measuring temperature. It suggests that everyone possesses a varying degree of bisexuality, which is more a preference with fluid boundaries than a strict identity.

The History of the Kinsey Scale

The defense of the Kinsey Scale was profoundly provocative during the 1940s and 50s. Based on thousands of questionnaires administered to diverse men and women, Kinsey’s study sparked intense controversy and fierce opposition from conservative institutions. Paradoxically, this backlash facilitated the rapid global dissemination of his ideas, with his writings and reflections translated into multiple languages.

The seminal Kinsey Reports, published as Sexual Behavior in the Human Male (1948) and Sexual Behavior in the Human Female (1953), presented data that fundamentally questioned prevailing understandings of human sexuality and gender. Drawing from information provided by 6,300 men and 5,940 women, Kinsey concluded that pure heterosexuality is exceptionally rare, if not almost non-existent, and should be considered an abstract concept serving as one extreme of a scale. The same applied to pure homosexuality, although this notion faced less resistance for obvious reasons. These findings implied that traditional masculine and feminine identities were, to some extent, fictional constructs, and many behaviors considered “deviant” were, in fact, common.

What the Scale Looks Like

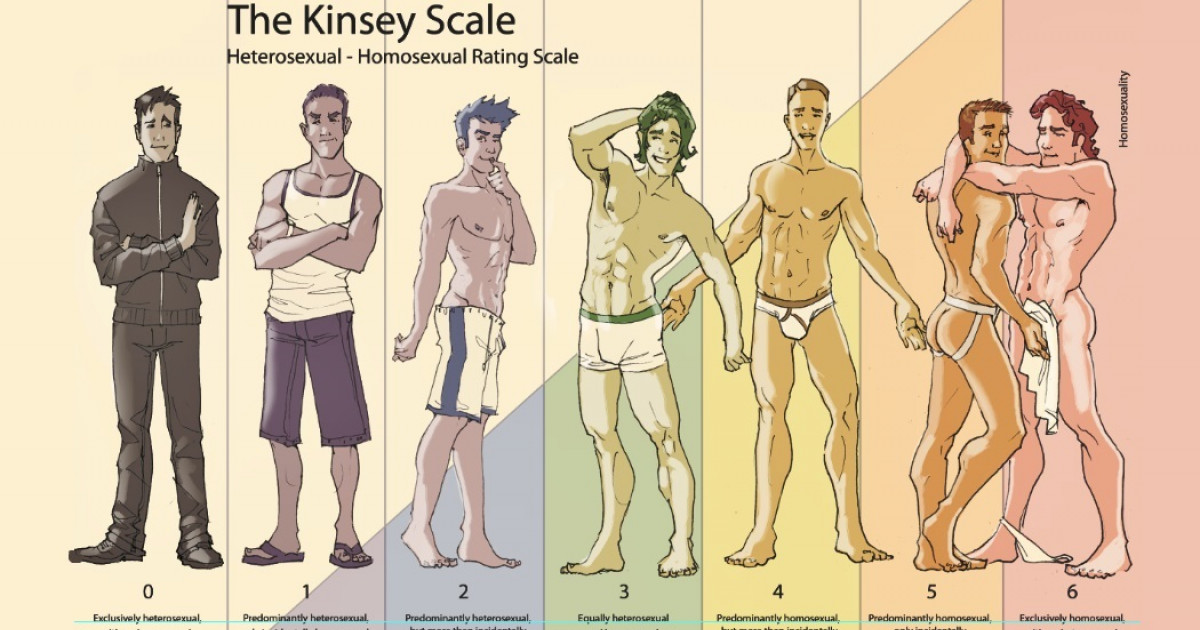

Kinsey’s innovative scale features seven degrees of heterosexual-to-homosexual orientation, plus an additional category for individuals not engaging in sexual relations. These degrees are:

- Exclusively heterosexual

- Predominantly heterosexual, incidentally homosexual

- Predominantly heterosexual, but more than incidentally homosexual

- Equally homosexual and heterosexual

- Predominantly homosexual, more than incidentally heterosexual

- Predominantly homosexual, incidentally heterosexual

- Exclusively homosexual

X. No socio-sexual contacts or reactions.

A Different Conception of the Human Mind

At its inception, the Kinsey Scale offered a transformative perspective on the human mind, particularly concerning sexuality. Historically, the division of labor and gender roles profoundly enforced a highly dichotomous view of what it means to be male and female. Kinsey’s research line critically challenged this rigid classification. Over the years, gender studies have leveraged the insights of this scale to highlight how **heteronormativity**, which centralizes heterosexuality as the norm, is an oversimplified and unjustified social construct. This construct often exerts social pressure on minority groups whose sexual orientations fall outside this normalized view.

The Kinsey Scale Today

Kinsey did not devise a seven-point scale because he believed there were exactly seven fixed steps in sexuality. Rather, he viewed it as a practical method to measure something inherently **fluid and continuous**. Consequently, his work profoundly influenced Western philosophy, reshaping our understanding of sexual orientations and positively impacting movements for equality and the fight against discrimination targeting homosexual individuals. Nevertheless, the debate about the nature of sexual orientations—whether they are best understood as a continuum or as distinct categories—remains vibrant.

This debate extends beyond pure scientific inquiry, as the social and political implications of the Kinsey Scale often lead to its perception as an ideological tool. Conservatives frequently view it as a threat to traditional nuclear family values and a component of “gender ideology.” Conversely, LGBTQ+ communities often embrace it as a valuable conceptual framework for studying sexuality with greater flexibility than conventional approaches.

Modifying the Approach to Studying Homosexuality

Furthermore, this scale of sexual orientations deemphasizes the concept of pure homosexuality and pure heterosexuality, effectively reducing them to theoretical constructs. This perspective significantly **reduces social pressure to conform to these two categories**. In essence, the Kinsey Scale established a precedent: the phenomenon under study shifted from homosexuality, often viewed as an anomaly or deviation, to the interactive relationship between homosexuality and heterosexuality. Previously, the focus was on a “rarity”; today, the goal is to comprehend a continuum with two distinct poles. It is important to acknowledge that Kinsey’s research had limitations and utilized methodologies that might be rejected today, reflecting the scientific standards of his era. However, the enduring legacy of his work is the powerful idea that sexual orientations cannot be confined to hermetic categories, and their boundaries remain diffuse and, to some extent, unpredictable.